Page 39 - Summer_2019

P. 39

ArchDC Summer 2019.qxp_Spring 2019 5/22/19 2:57 PM Page 37

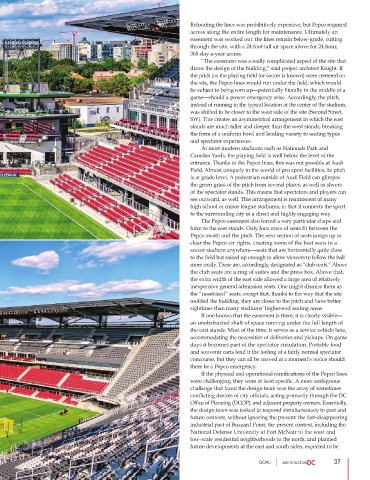

Relocating the lines was prohibitively expensive, but Pepco required

access along the entire length for maintenance. Ultimately an

easement was worked out: the lines remain below-grade, cutting

through the site, with a 24-foot-tall air space above for 24-hour,

365-day-a-year access.

“The easement was a really complicated aspect of the site that

drove the design of the building,” said project architect Knight. If

the pitch (as the playing field for soccer is known) were centered on

the site, the Pepco lines would run under the field, which would

be subject to being torn up—potentially literally in the middle of a

game—should a power emergency arise. Accordingly, the pitch,

instead of running in the typical location at the center of the stadium,

was shifted to be closer to the west side of the site (Second Street,

SW). This creates an asymmetrical arrangement in which the east

stands are much taller and deeper than the west stands, breaking

the form of a uniform bowl and lending variety to seating types

and spectator experiences.

At most modern stadiums such as Nationals Park and

Camden Yards, the playing field is well below the level of the

entrance. Thanks to the Pepco lines, this was not possible at Audi

Field. Almost uniquely in the world of pro sport facilities, its pitch

is at grade level. A pedestrian outside of Audi Field can glimpse

the green grass of the pitch from several places, as well as slivers

of the spectator stands. This means that spectators and players can

see outward, as well. This arrangement is reminiscent of many

high school or minor league stadiums, in that it connects the sport

to the surrounding city in a direct and highly engaging way.

The Pepco easement also forced a very particular shape and

form to the east stands. Only four rows of seats fit between the

Pepco swath and the pitch. The next section of seats jumps up to

clear the Pepco air rights, creating some of the best seats in a

soccer stadium anywhere—seats that are horizontally quite close

to the field but raised up enough to allow viewers to follow the ball

more easily. These are, accordingly, designated as “club seats.” Above

the club seats are a ring of suites and the press box. Above that,

the extra width of the east side allowed a large area of relatively

inexpensive general admission seats. One might dismiss them as

the “nosebleed” seats, except that, thanks to the way that the site

molded the building, they are closer to the pitch and have better

sightlines than many stadiums’ higher-end seating areas.

If one knows that the easement is there, it is clearly visible—

an unobstructed shaft of space running under the full length of

the east stands. Most of the time, it serves as a service vehicle lane,

accommodating the necessities of deliveries and pickups. On game

days it becomes part of the spectator circulation. Portable food

and souvenir carts lend it the feeling of a fairly normal spectator

concourse, but they can all be moved at a moment’s notice should

there be a Pepco emergency.

If the physical and operational ramifications of the Pepco lines

were challenging, they were at least specific. A more ambiguous

challenge that faced the design team was the array of sometimes

conflicting desires of city officials, acting primarily through the DC

Office of Planning (DCOP), and adjacent property owners. Essentially,

the design team was tasked to respond simultaneously to past and

future contexts, without ignoring the present: the fast-disappearing

industrial past of Buzzard Point; the present context, including the

National Defense University at Fort McNair to the west and

low-scale residential neighborhoods to the north; and planned

future developments at the east and south sides, expected to be

GOAL! 37